Clarity Unbound

Restoring Radiance to Information Design

Clarity has two faces: lucid makes meaning clear, luminous makes it sing. Information excels when it has both—but lately luminous clarity has slipped out of frame.

Lucid clarity conjures clearness: clear judgment, clear intellect, and clear conscience. Clearness of sight and clearness of sound.

English polymath Thomas Browne heard it in the “clarity of their understanding” (Pseudodoxia Epidemica, 1646). Millennia earlier, Aristotle emphasized that the proper function of style is to make the meaning clear (Rhetoric III-2). That’s lucid clarity.

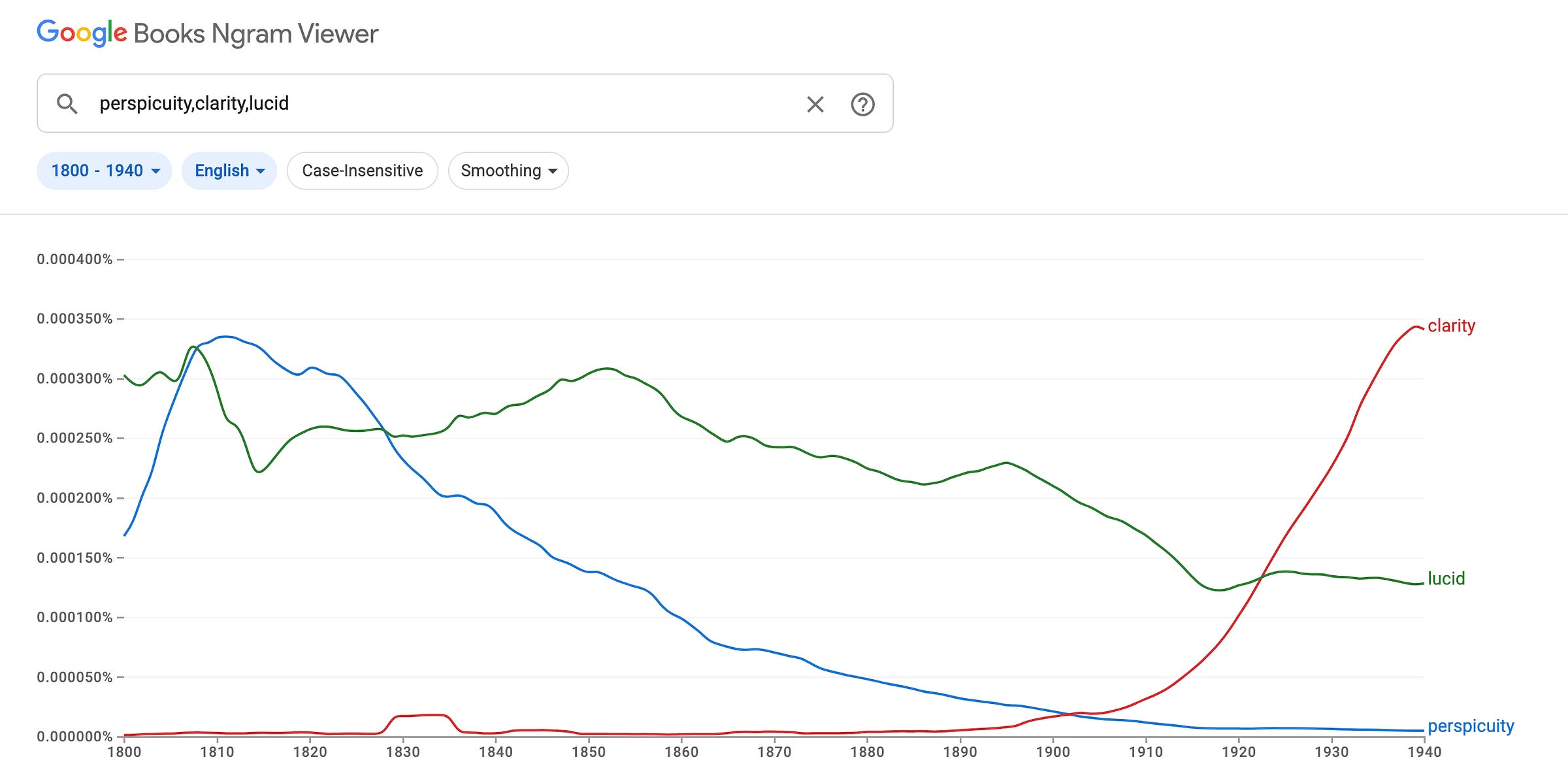

Designers long called this duty perspicuity—transparent expression in the service of understanding. You may not know that word. (I didn’t.) See below how 🔴CLARITY’s popularity has risen in the wake of 🔵PERSPICUITY’s decline.

This switch helps us better appreciate the subtitle of William Playfair’s Statistical Breviary (1801): “Charts Representing Physical Powers … with Ease and Perspicuity.” Today, Playfair would say “with clarity.”

The modern and partial understanding of clarity, lucid clarity, is simply perspicuity. Metaphorically, think of lucid clarity as a polished window. It is the kind of frame that lets you see what’s going on uninhibited: clean, efficient, simple, and obvious (once you see it).

But clarity is never actually used to describe a window. When we grade something on its clarity we are admiring diamonds, not windows.

Lucid clarity’s triumph feels total. Yet something vital is missing.

Today, the demand for lucid clarity is ever louder as attentiveness and concentration shrivel under the pressure of digital media.

Lucid clarity’s insistence on easy insights makes no room for the intricacies of reality. Lucid clarity has little appreciation for astonishment, amazement, and wonder.

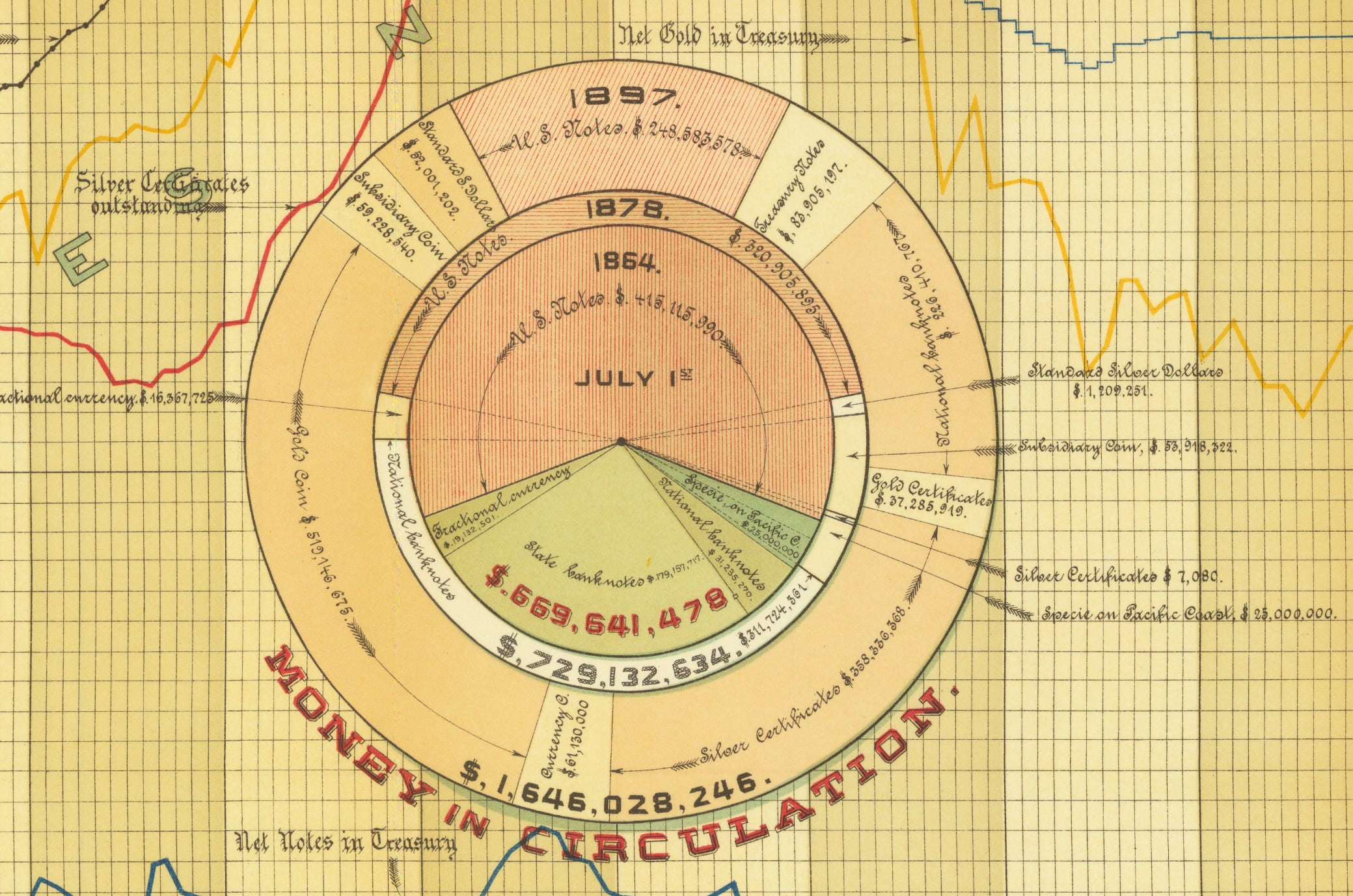

For example, lucid clarity has no way of acknowledging why I am attracted to fantastical historic attempts, like this detail from the U.S. Treasury Department (1897, BLR). This polar diagram offers little in the department of “clear meaning,” yet it still excites me to look:

One hazard of chasing lucid clarity is confusing presentation and understanding. Graphic efficiency is only loosely related to effective reading. Don’t mistake the messenger for the message.

The essential clarity, like all meaning and value, lives in the mind of the viewer. A clearly-expressed chart alone in the woods inspires no clarity.

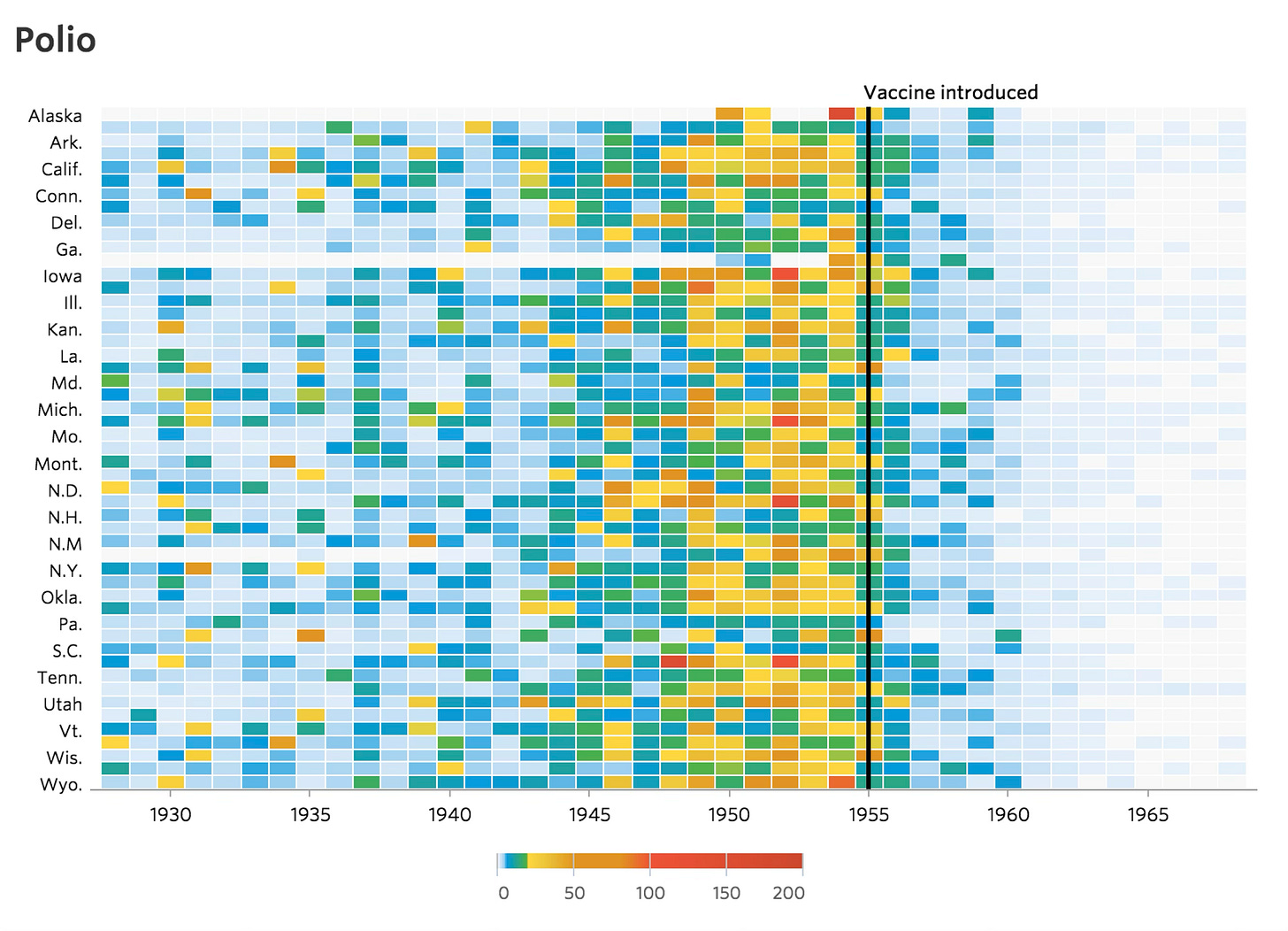

Simple truths aren’t always best served by plain design. Here are two treatments of the same data—one lucid, one luminous.

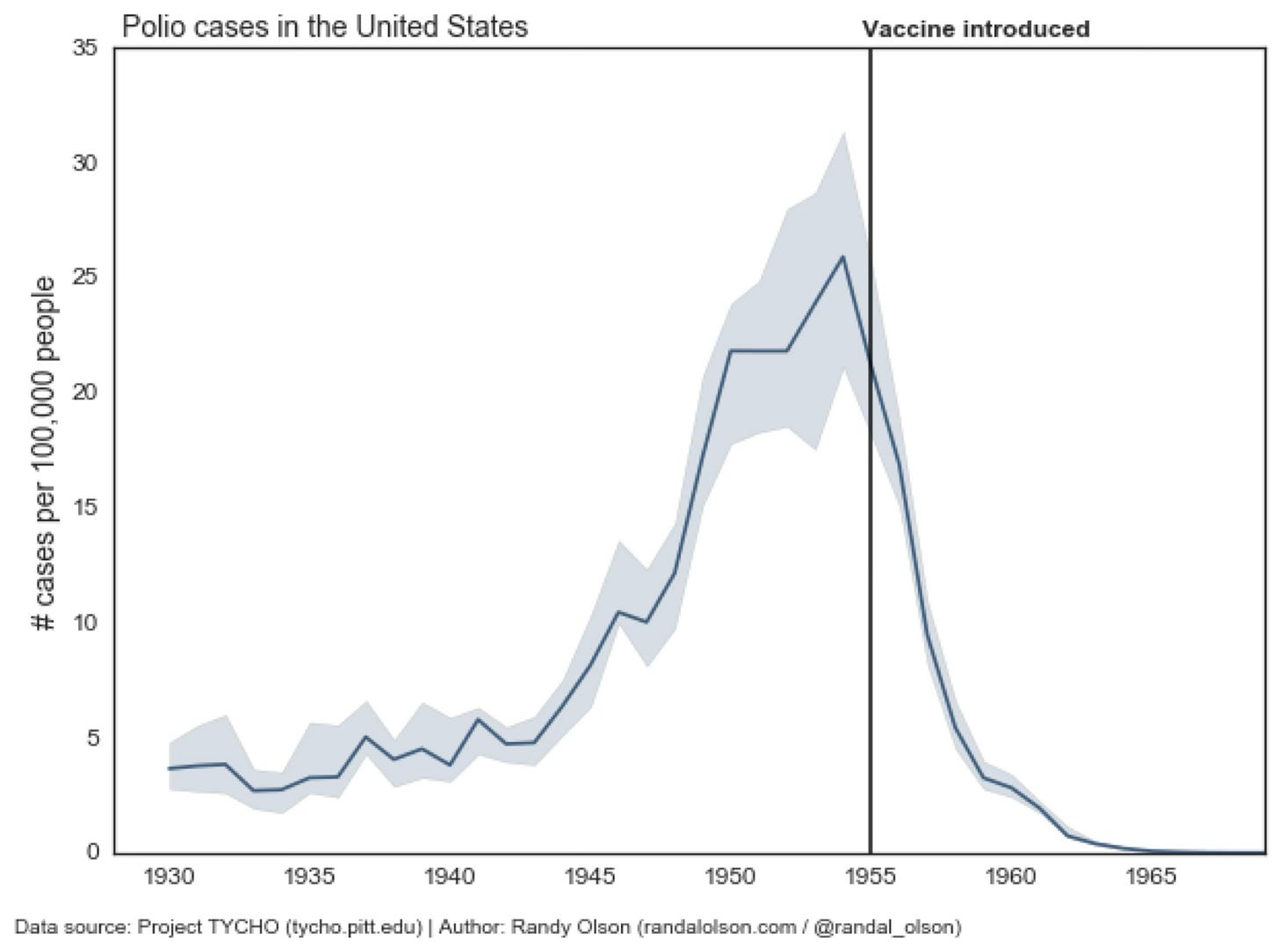

In the lucid example below, a single line averages the story into one curve. It’s graphically efficient and makes a crisp claim.

This line graph was created by Randy Olson to spotlight attributes of the Wall Street Journal original:

Perhaps the lucid line graph makes a clearer argument. But it lacks that mysterious thing that the luminous original radiates with. The table texture is exciting, which makes its post-vaccine silence more powerful.

Simple truths are not always best conveyed through plain design. This point is sometimes made through the rebuke of analytic lenses like “data–to–ink ratio.” Lucid-clarity obsessives might have us refrain from the funfetti spectacle of the disease-incidence table. But when clarity is reduced to frictionless decoding, gratification of mind departs.

Our world feels awash in information windows but devoid of information diamonds.

Lucid clarity, modern clarity, is not wrong. But it is incomplete.

Lucid clarity makes charts easy to read—light as spotlight. Luminous clarity uses light as architecture. It makes things worth inhabiting.

If we look deeper into clarity’s history, we see these richer qualities: brightness, luster, radiance, splendor, and glory. Clarity is not merely clear thought. It is also spiritual illumination.

Greek philosopher Plotinus gives the luminous sense: clarity as radiance that seizes the knower. “What is it that attracts the eyes of those to whom a beautiful object is presented, and calls them, lures them, towards it, and fills them with joy at the sight?” (Enneads, c. AD 250)

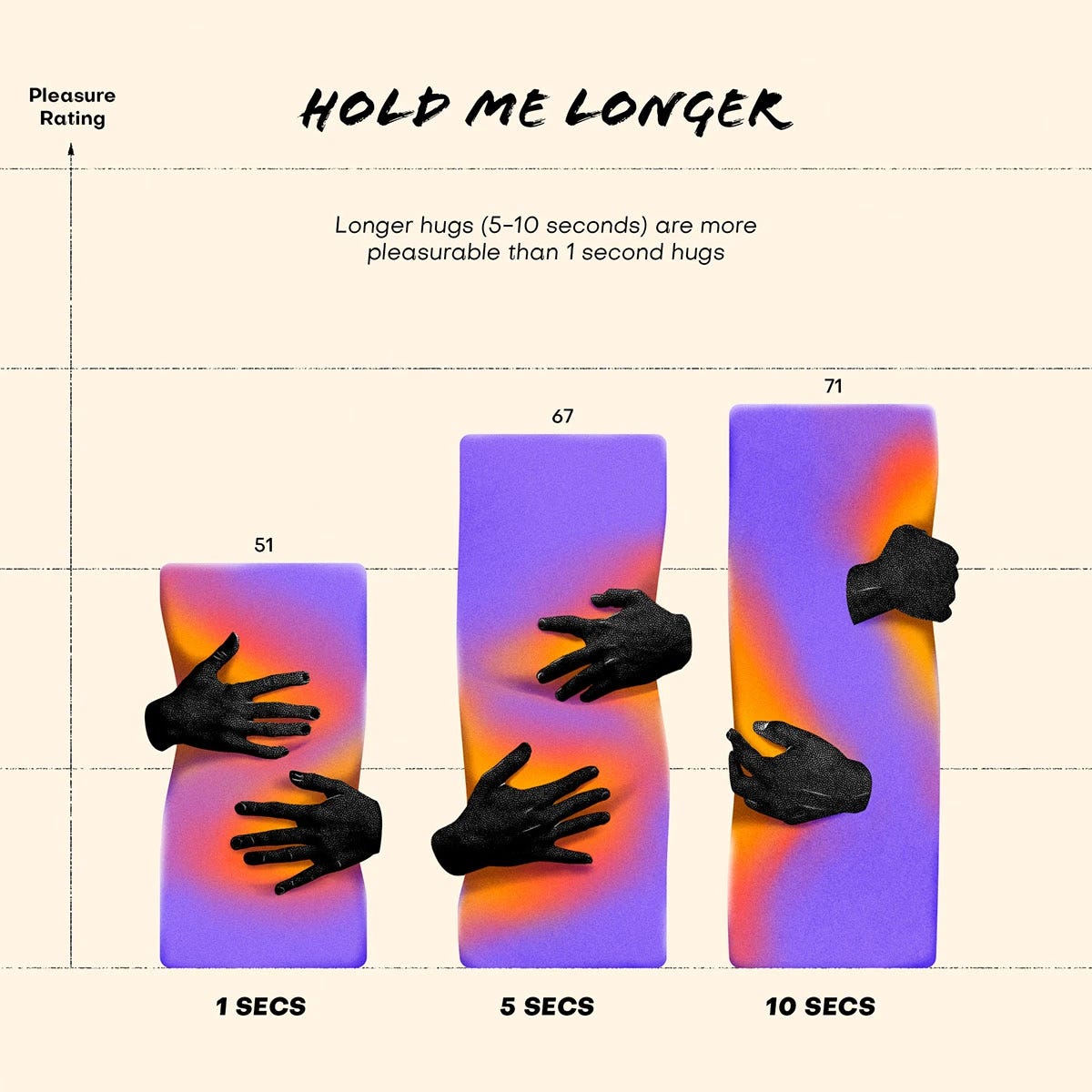

Gabrielle Merite’s much-loved hug chart, above, fills me with that joy. From my perspective, it isn’t differentiated by its lucidity, but by its extravagant luminosity.

Here again, it is easy to confuse messenger and message. The glowing attributes of her composition and the luminous clarity it encourages in me are related, but not the same. The supreme glow is the one inside.

Plotinus described entering into union with knowledge as beautiful: thrilled with delight, stirred to harmonious coherence and affinity with splendor beyond material bodies. “This is the spirit that Beauty must ever induce, wonderment and a delicious trouble.”

The eyelids close; yet a light flashes before us. … All that one sees as a spectacle is still external; one must bring the vision within and see no longer in that mode of separation but as we know ourselves; thus a man filled with a god—possessed by Apollo or by one of the Muses—need no longer look outside for his vision of the divine being; it is but finding the strength to see divinity within.

Suddenly, swept beyond it all by the very crest of the wave of Intellect surging beneath, he is lifted and sees, never knowing how; the vision floods the eyes with light, but it is not a light showing some other object, the light is itself the vision. … Radiance.

Now, Plotinus was not specifically describing the sensation of reading a bar chart, but his words resonate with how I understand the magic of information graphics. Illumination does not stop at shining the light on something else, illumination swells when your own soul becomes one with the light it perceives.

Clarity is light worth beholding.

Knowing used to be godliness.

Think of knowledge as unification with a power beyond our corporeal form. This resonates with my excitement for the possibility of datasets: Knowledge lets us grasp something bigger than ourselves. Data lets us stretch across vast space and time, giving us vision to phenomena impossible for any single person to ever experience on their own.

German polymath Hildegard of Bingen provides a striking example of luminous clarity. She was a twelfth century abbess now credited as a founder of scientific natural history. She is also famous for visions, possibly the result of migraine headaches, which she described and illustrated. Read about one of her visions from Scivias (c.1151):

I saw a great mountain the color of iron, and enthroned on it One of such great glory that it blinded my sight. Before him, at the foot of the mountain, stood an image full of eyes on all sides, in which, because of those eyes, I could discern no human form. In front of this image stood another, a child wearing a tunic of subdued color but white shoes, upon whose head such glory descended from the One enthroned upon that mountain that I could not look at its face. But from the One who sat enthroned upon that mountain many living sparks sprang forth, which flew very sweetly around the images.

… He Who was enthroned upon that mountain cried out in a strong, loud voice saying, “O human, who are fragile dust of the earth and ashes of ashes! … Burst forth into a fountain of abundance and overflow with mystical knowledge, until they who now think you contemptible because of Eve’s transgression are stirred up by the flood of your irrigation. For you have received your profound insight not from humans, but from the lofty and tremendous Judge on high, where this calmness will shine strongly with glorious light among the shining ones.

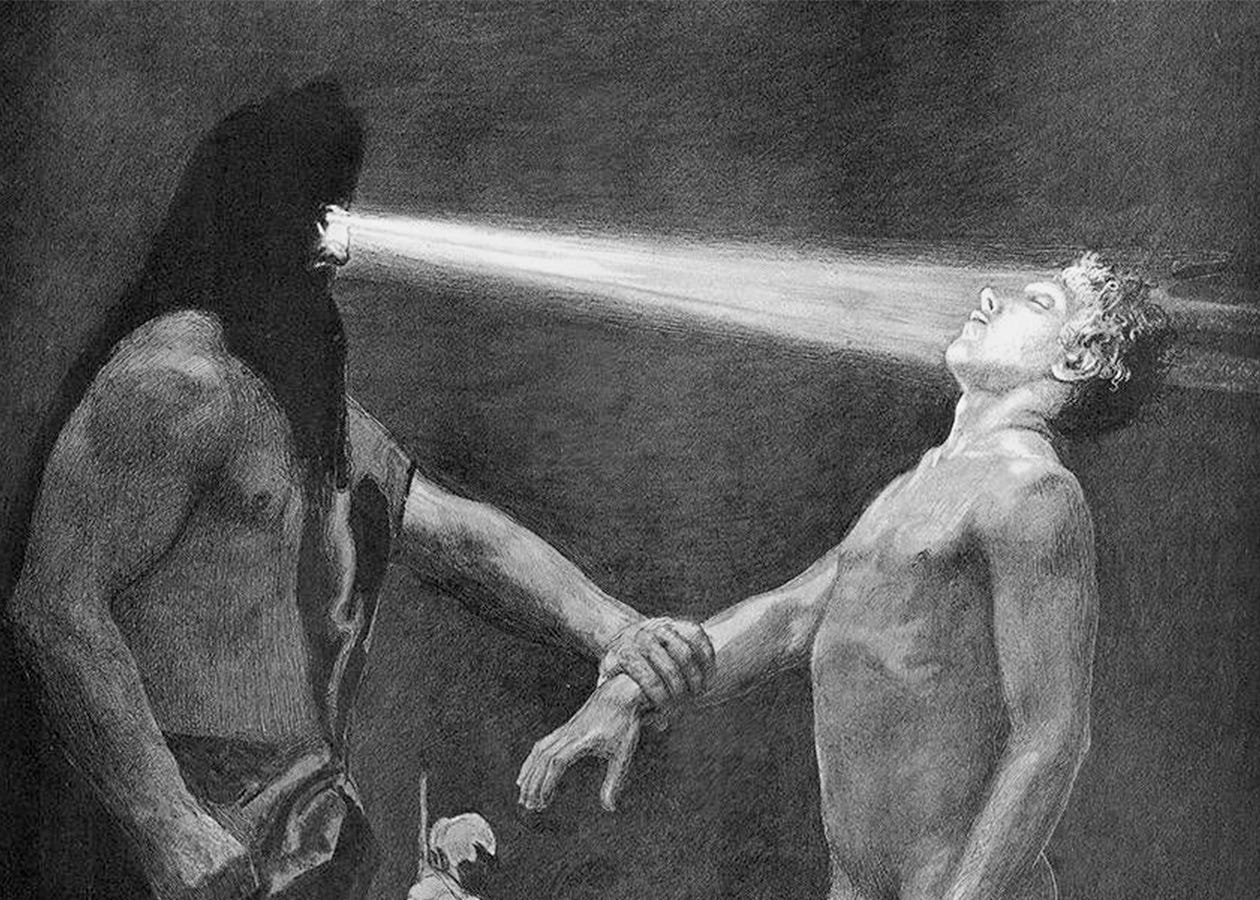

And here is that vision illustrated. Note the blue figure, clothed in eyes—vigilant awe made visible.

Hildegard’s vision shows what luminous clarity feels like—a blazing union of seer and splendor. It also echoes the medieval account of phantasia (the inner “imagination”), later dramatized by Dante as images that “rained into [his] high imagination” (Purgatorio XVII, 25).

About a century after Hildegard, Thomas Aquinas named beauty’s three marks: integritas, consonantia, claritas: wholeness, proportion, and radiance.

Cautions

In his meditations, René Descartes further distinguished the separation of perception and knowledge, seer and truth:

I am so amazed that I can neither touch the bottom, nor swim at the top. … I am a Thinking Thing, that is to say, doubting, affirming, denying, understanding few things, ignorant of many things, willing, nilling, imagining also, and sensitive.

Whatever I clearly and distinctly perceive is certainly true. But I have formerly admitted many things as very certain and manifest, which I afterwards found to be doubtful.

Descartes cautions us against blind faith in clarity. Clear perception with our senses is not a guarantee of truth. “I know not, whether they are true or false, that is to say, whether the ideas I have of them are the ideas of things which really are, or are not.”

You may look with perfect vision to the night sky. But what you see is not perfectly true. Try again, this time with a telescope.

We last heard Aristotle endorsing perspicuity, the importance of clear meaning. He also adds an ethic about proportion of emphasis. Proper style requires the appropriate amount of splendor. Grandeur about trivialities rings false. Blinding radiance misleads, or worse: overpowers, oppresses, dominates.

Yet, I am wary we’ve lost too much illumination via too much mechanical efficiency.

Take care to not over-decorate, sure. But that is hardly a risk today. I feel lost in a Flatland where there’s a lot of everything and it all feels the same.

Italo Calvino touched on this in his short story “How much shall we bet?” (Cosmicomics, 1968), where an eternal being longs to be again at the beginning of creation:

And I think how beautiful it was then, through that void, to draw lines and parabolas, pick out the precise point, the intersection between space and time where the event would spring forth, undeniable in the prominence of its glow; whereas now events come flowing down without interruption, like cement being poured, one column next to the other, one within the other, separated by black and incongruous headlines, legible in many ways but intrinsically illegible, a doughy mass of events without form or direction, which surrounds, submerges, crushes all reasoning.

We are drowning in Calvino’s doughy mass of events. I yearn for the revitalization of his prominent glow.

Like past generations who reacted to industrialization by turning to the unity of light, body, and soul, I re-embrace clarity. I am now able to seek beyond clear thinking. Clarity is both lucid and luminous, both perspicuous and radiant. I seek the treasure that concludes the 1989 adventure film “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.”

Indiana Jones: What did you find, Dad?

Dr. Henry Jones, Sr.: Me? Illumination.

Onward!—RJ

Welcome to Chartography.net — insights and delights from the world of data storytelling.

This summer, we republished a series of historic writing about information design. It is the SUMMER OF CLARITY! These essay inspired the blue marginalia in my new book Info We Trust ($39 from Visionary Press).

About

RJ Andrews helps organizations solve high-stakes problems by using visual metaphors and information graphics: charts, diagrams, and maps. His passion is studying the history of information graphics to discover design insights. See more at infoWeTrust.com.

RJ’s book, Info We Trust, is currently out now! He also published Information Graphic Visionaries, a book series celebrating three spectacular data visualization creators in 2022 with new writing, complete visual catalogs, and discoveries never seen by the public.

OMG RJ, you've done it again. No, let me be more lucid; you've outdone yourself this time.

The sheer amount of insight, intellect, illumination, joy, and oh-so-quotable-quotes is this post is extraordinary.

You have become the master.

Now, with the bar set so high, I look forward to seeing how you continue to jump over it.