"Completely New Perspectives—More Eloquent and Richer than All Others"

Physicist Felix Auerbach's 1914 introduction to graphic representation.

Welcome to Chartography.net — insights and delights from the world of data storytelling.

This summer, we are showcasing a series of historic writing about information design. It is the SUMMER OF CLARITY! These essay inspired the blue marginalia in my new book Info We Trust ($39 from Visionary Press).

Today, enjoy the 1914 introduction to Felix Auerbach’s Die graphische Darstellung [The graphic representation], translated with some help from DeepL and augmented with new photography of its page spreads

Graphic Representation

Method plays a tremendous role not only in science, but also in the practice of life, in technical, political, cultural and finally in everyday life. Don't we constantly hear people talking about methods and arguing about which of them is the best? Of methods of thinking and acting, of educational methods, of methods of physical exercise? He who has a method achieves his goal; he who has no method fails, even if his cause is excellent in principle and its implementation is desirable in the personal or general interest.

A distinction must be made between two types of methodology: there are methods for discovering new things, inventing new things, conquering new things; methods that can be described as synthetic methods. And on the other hand, there are analytical methods, the importance of which is to clarify and secure existing or newly acquired knowledge and to overlook the possibilities of its consequences and useful applications. Not, of course, that there is a sharp distinction between the two genres; in particular, the analytical method will in most cases also be fruitful for positive progress; after all, cognition and action, analysis and synthesis are intimately connected everywhere in the world.

The method to be discussed in this book belongs to the second type: it is a method of presenting recognized phenomena, facts, truths, and ideas in such a way that they speak directly for themselves; that everyone who has learned to understand the language of presentation is able to grasp and process what is presented to him independently and autonomously. It is therefore a method of practice, albeit understood in the broadest sense: equally valuable for abstract science, which thereby strips away its abstract nature as far as possible, and for things of general interest in nature, culture and technology. And precisely because it is a practice, it is desirable, and almost essential, to lay the foundations deeply and to be clear about what the method means and how it has come to play the role it does today.

Among the faculties of the human mind, whose diversity stands in strange contrast to its postulated unity, two stand out in terms of general significance: abstract thinking and direct intuition. The order in which these two abilities are listed is a concession to the historical development and the appreciation that has not yet been completely overcome, especially in scientific circles. Abstract thinking, in contrast to the naive man's attitude towards his environment and inner world, has taken the lead during whole and long periods of mankind's scientific history, and it still finds its almost pure expression in the educational plan characterized by the humanistic grammar schools. And yet the other side of intellectual methodology, intuition, is not only on an equal footing with the other, but on closer inspection proves to be dominant on both sides: on the side of the root, inasmuch as abstract thought also proceeds somewhere from an intuition transmitted by sense perception, as, of course, intellectual researchers do not always know or want to know, and upwards, inasmuch as the results of pure thought also require a language through which they can first become common property, and which in turn is nothing other than a form of perception in the broadest sense, not limited to the eye. Language and writing, the physical or planar image, the geometric line and many others: these are only different forms in which the result of mental work can communicate itself and thus attain an existence that extends beyond the inner life of the producer.

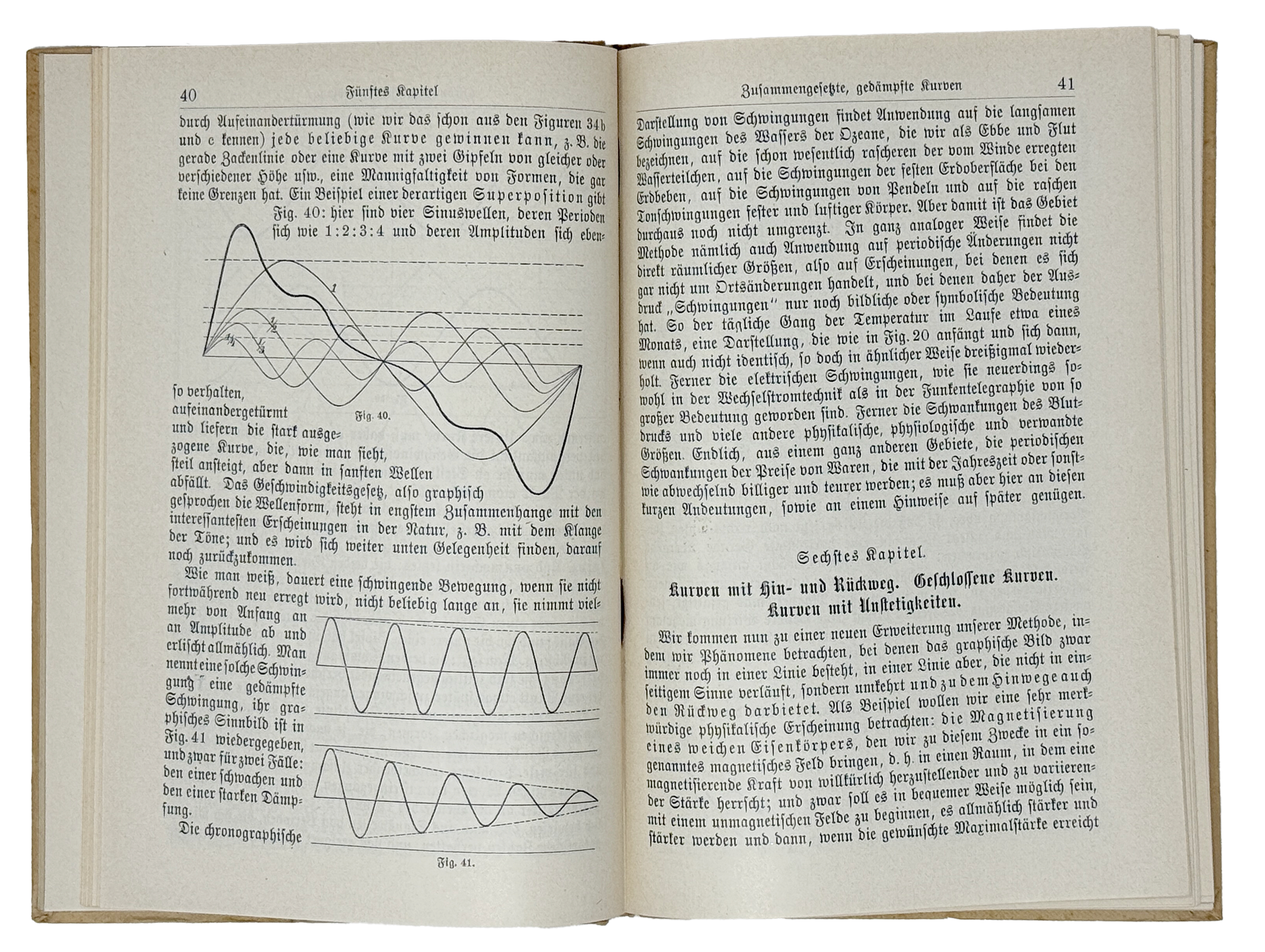

In exact science, after long periods of purely abstract speculation, this realization has of course repeatedly won the day, and for some time now it has only been disputed by fanatics of the other school. Visualization, both external and internal, the perception of things in vivid images before the physical or mental eye, has enriched research and knowledge in unexpected ways and in many cases opened up completely new perspectives. Language, for its part, has been brought into ever more scientific form and has reached its peak in the mathematical language of formulae. This represents the phenomena of the external world and, as far as it has succeeded so far, the internal world through a combination of mathematical quantities, some of which are functions of others, i.e. change with them when they change; and this in a purely factual way, without saying anything about the so-called causal side of things, which would initially only be hypothetical. From the formula one can then deduce backwards individual numerical values and whole series of numbers and gain control over the system by comparison with what direct observation reveals. After all, even these means of expression, the series of numbers and the formulas, are still abstract in a certain sense and only vivid for those who have worked their way up to this form of perception through long practice and an overview of the nature of matter that has already become a habit.

There is an aid of even greater vividness, and it is based on an idea that is perhaps quite remote at first, but which, once grasped, immediately reveals its immense fertility. For all spatial things in the world we have, thanks to the organization of our eye, an exceptional method that is quite incomparable: the production of images. Not only is the entire science of the physical based on this, i.e. everything that is still often referred to as natural history, but also the great and high field of the fine arts, in which man productively uses this ability. Everything else that confronts us in the surrounding and inner world is beyond our spatial perception; we can only grasp it by thinking, but not by representing it. How, then, if we were to remedy this natural deficiency artificially, if we were to decide to grasp and depict non-spatial things, e.g. temporal things and everything that relates to temperature and electricity, to brightness and color, to material and spiritual quantity and quality and to hundreds of other things, under the image of the spatial? It is reasonable not to demand too much here immediately; but this much is obvious: nothing that has been precisely grasped, nothing that can be specified as a functional relationship, is beyond the scope of the method in question—in principle, of course; the development into a real procedure is a matter in itself and must be thought out and tested step by step.

This is the foundational and objective basic idea of what is currently called the method of graphic representation. An outwardly undemanding art, for it presents the eye with nothing but lines and groups of lines and, again and again, lines, sometimes also surfaces and, in extreme cases, spatial, model-like figures. But for those who know how to read this language, it is in its own way more eloquent and richer than all others; it tells an incredible amount in a small space; for one can read this writing, so to speak, from the front and back, from above and below, analytically and synthetically; and each time one receives the same insight in a new form, a new context, a new genesis, and that, after all, is always a new insight. No wonder that graphic representation, whose earlier neglect can only be explained by the oppressive tyranny of the abstract modes of thought, has in recent and most recent times undertaken a veritable triumphal march through all areas of scientific research, starting from the exact natural sciences and the statistical-economic disciplines and gradually conquering even the brittlest and most brittle terrain, until it has finally reached the heart of psychology and philosophy.᠅

Felix Auerbach (1856–1933) was a German Jewish physicist and early campaigner for women’s suffrage. A Bauhaus supporter, his Walter Gropius-built house, The Auerbach House, was a cultural center for artists and scientists. The rise of Adolf Hitler and the anti-Semitic climate in Germany made life unbearable for Felix and his wife Anna. After the Nazis seized power, both took their own lives. In his suicide note he stated that they "left the earthly life full of joy, after nearly 50 years of mutually blissful cohabitation."

See Auerbach’s original text: https://archive.org/details/AuerbachDieGraphischeDarstellung/page/n1/mode/2up

Let me know if you can help improve this translation, or have suggested entries for future editions of THE SUMMER OF CLARITY.

Translation ©2025 RJ Andrews. All rights reserved.

About

RJ Andrews helps organizations solve high-stakes problems by using visual metaphors and information graphics: charts, diagrams, and maps. His passion is studying the history of information graphics to discover design insights. See more at infoWeTrust.com.

RJ’s book, Info We Trust, is currently out now! He also published Information Graphic Visionaries, a book series celebrating three spectacular data visualization creators in 2022 with new writing, complete visual catalogs, and discoveries never seen by the public.

Quickly, I can add an interesting semantic point about translating the word Darstellung. The substantive version of the concept in German is usually translated in English as Representation. However, as German usage of the verb "darstellen" suggests, "presentation" might be better in an art or design context when referring to the activity rather than the product. That said, representation is probably still the better term for most art history and philosophy. It involves the embodied relationship between the actions and the object, as well as the concepts. If the difference between presentation and representation is significant for the English author/translator, then the semantics can be substantial. Translations of Klee's Pedagogical Sketchbook are interesting in this regard.

A similar problem exists in translations of the word "Geistige" to "spiritual" (as in the title of one of Kandinsky’s books), because, when contextualised, you could arguably also translate it as "mental"; however, that word has too many meanings in both German and English, which are dissonant with Kandinsky’s intentions. More awkward, but better fitting, is probably mindfulness. That would lead to quite a different title for the book, then: “About mindfulness in art, especially painting”. I think that’s more in line with what he was actually teaching at Bauhaus first in Weimar, than in Dessau, just a few years after the book's publication.

Great article, as always. I wonder whether Auerbach's ‘semiotic’ remarks are not the result of the proto-Gestalt researches by his doctoral supervisor, Hermann von Helmholtz.