"The Eyes of History"

DuBourg hijacks the tools of cartography to visualize time.

Welcome to Chartography.net — insights and delights from the world of data storytelling.

This summer, we are showcasing a series of historic writing about information design. It is the SUMMER OF CLARITY! These essay inspired the blue marginalia in my new book Info We Trust ($39 from Visionary Press).

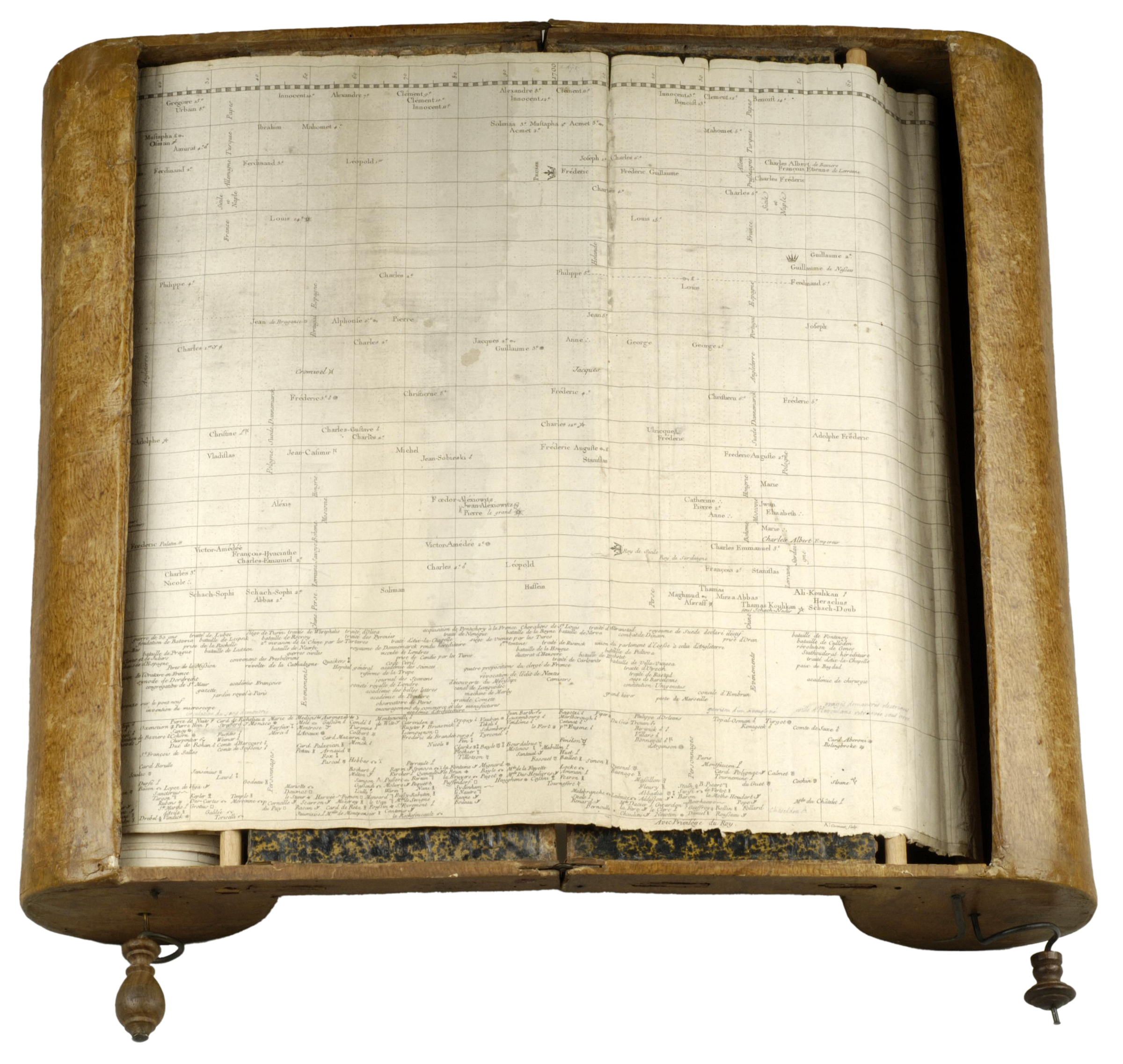

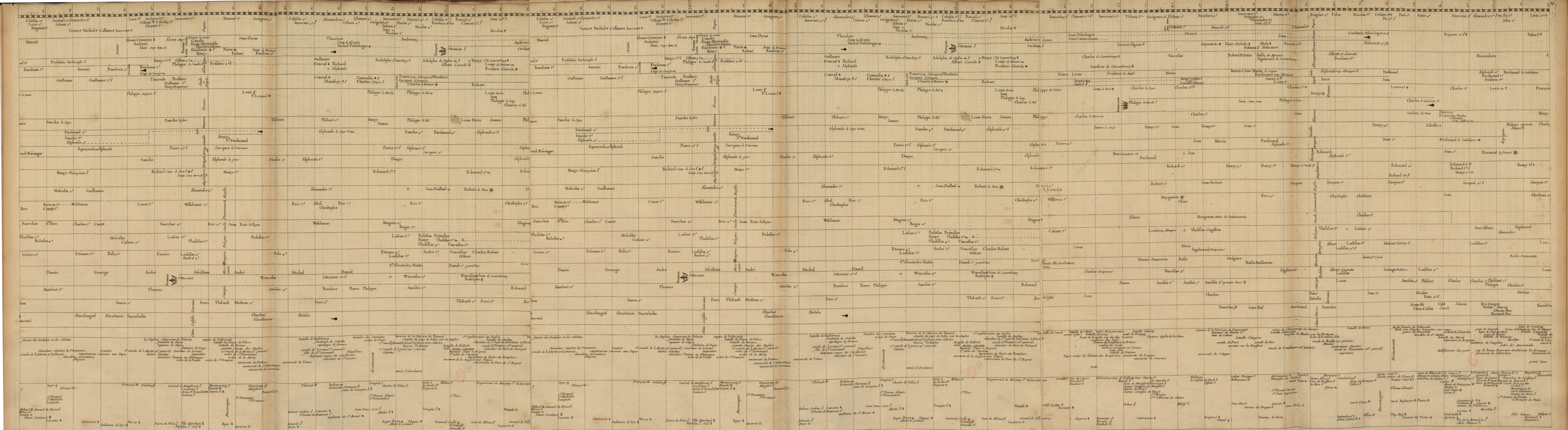

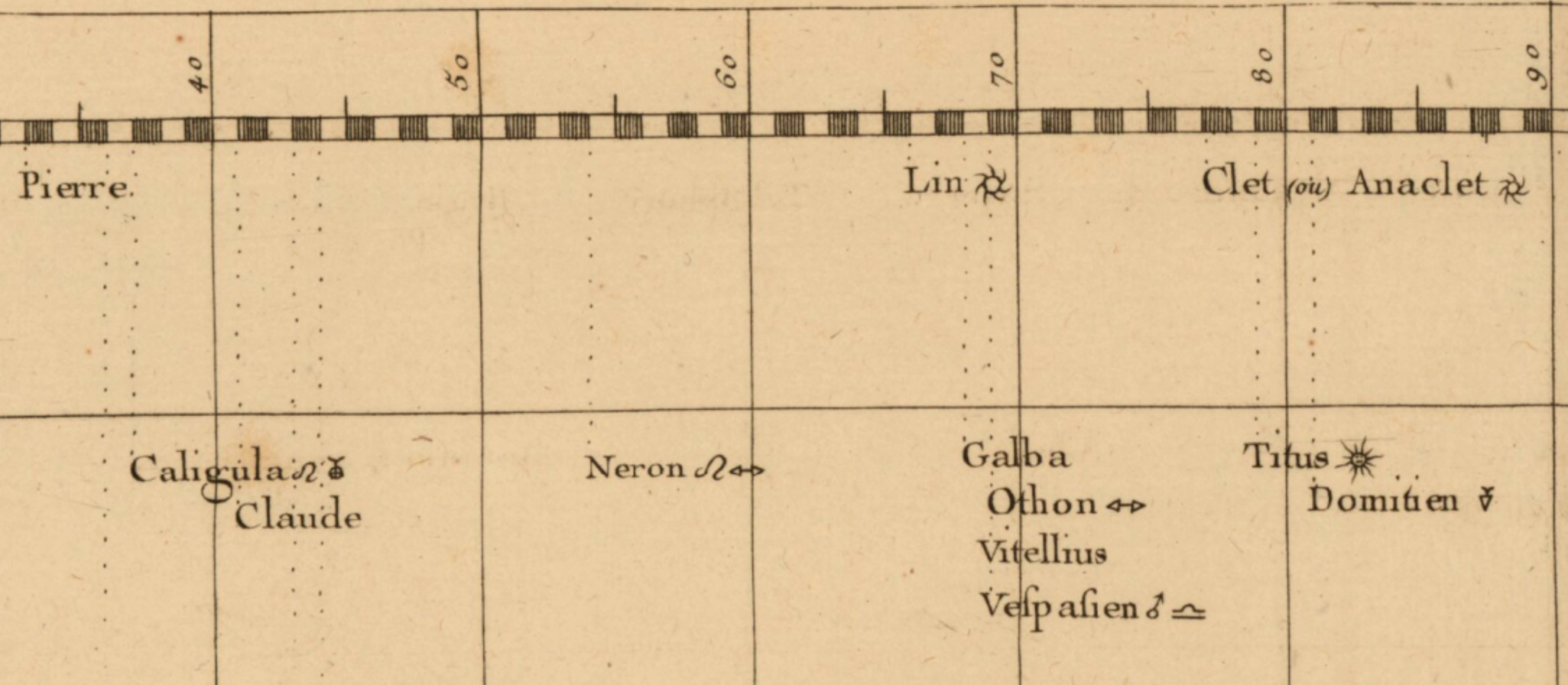

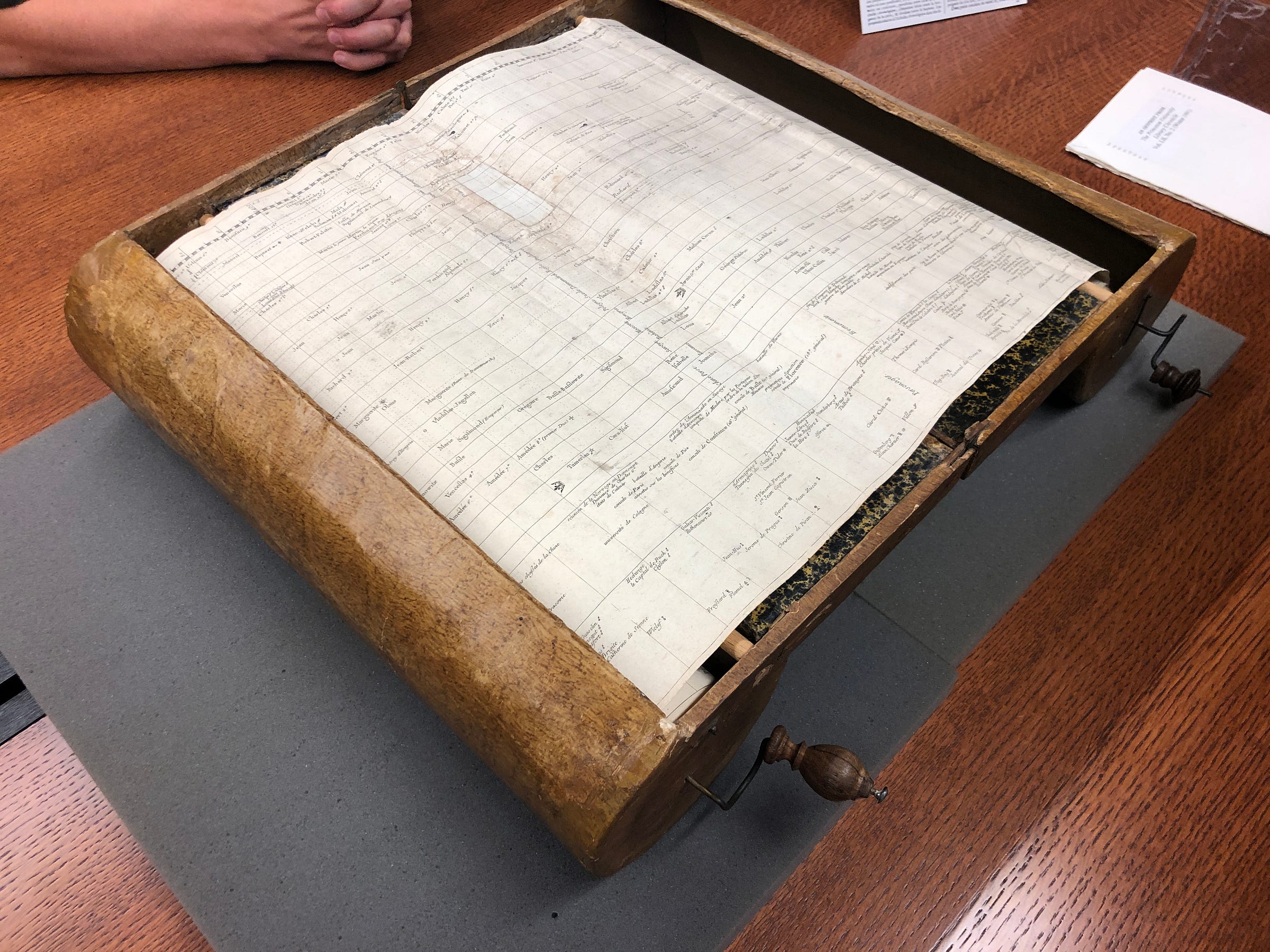

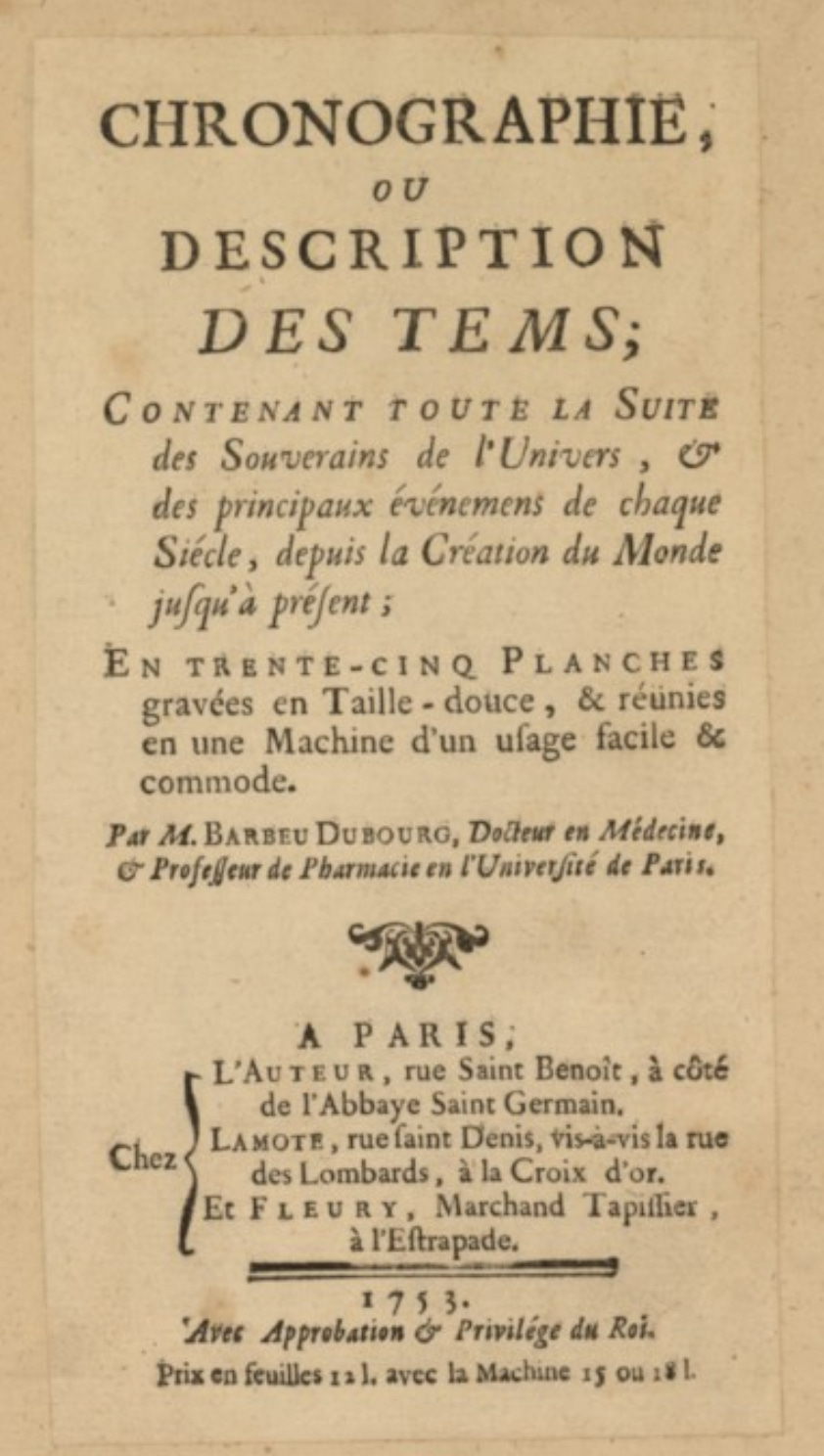

In 1753, Jacques Barbeu-Dubourg published a 54-foot timeline of history on an unbroken scroll. It included names and descriptive events, grouped thematically, with symbols denoting character and profession. The timeline could be purchased in a custom folding container—a “chronographic machine”—with cranks to advance the scroll, showing a 140-year window of history at a time.

The scroll is a milestone work from a period experimenting with ways of regularizing the representation of time. Daniel Rosenberg described that “Barbeu-Dubourg constructed one of the first charts that can properly be understood as a timeline.”

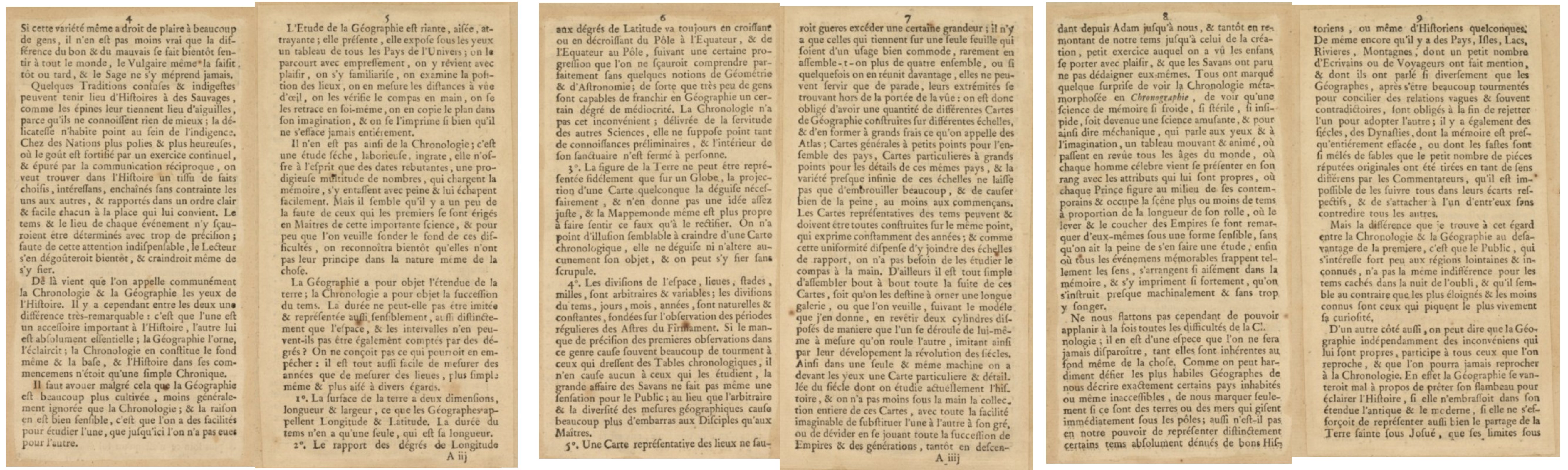

Today, enjoy Barbeu-Dubourg’s 1753 corresponding explanatory pamphlet, translated with some help from DeepL and augmented with my comments in square brackets and images from his iconic timeline.

Chronography, or Description of the Times

A taste for history is natural to all men, and its usefulness is perhaps the least disputed thing in the world. Indeed, what is History? It is the compendium of all that the eyes have seen, of all that the ears have heard; it's an enchanted school, where we learn at the expense of our teachers, where we censure others without compromising ourselves, where we learn to judge the past, to discern the present and to foresee the future, where one's experience is tested against that of all times, all countries, all ages and all states of life; where, finally, as reason develops and the mind opens to truth, morals become more gentle and the heart becomes firmly attached to virtue.

But this vast Field [of history] requires some cultivation, and as it has not received the same attention to all its parts, we shouldn't be surprised that its products are so different. Here you see charming flowers, there delicious fruit, elsewhere weeds are confused with wheat, and further on it's just arid, uncultivated soil. While this very variety may please many people, it's no less true that the difference between good and bad is soon felt by everyone, even the common man grasps it sooner or later, and the wise Sage never misunderstands it.

For Savages, a few confused and indigestible Traditions can take the place of Histories, just as thorns take the place of needles, because they know nothing better; delicacy does not dwell in the bosom of indigence. In more polite and happier nations, where taste is strengthened by continual exercise, and refined by mutual communication, we want to find in History a fabric of selected, interesting facts, linked without constraint to one another, and reported in a clear and easy order, each in its proper place. The time and place of each event cannot be determined with too much precision; without this indispensable attention, the reader will soon become disgusted with it, and even fear to trust it.

This is why Chronology and Geography are commonly referred to as the eyes of History. There is, however, a very notable difference between the two: one is an important accessory to History, the other is absolutely essential to it; Geography adorns it, enlightens it; Chronology is its very substance and basis, and History in its beginnings was no more than a simple Chronicle.

Despite this, it must be admitted that Geography is much more cultivated and less generally ignored than Chronology; and the reason for this is quite obvious: we have the facilities to study one, which we have not had up to now for the other.

The study of Geography is cheerful, easy and attractive; it presents a picture of all the countries in the Universe; you go through it with eagerness, you come back to it with pleasure, you become familiar with it, you examine the position of places, you measure their distances with your eyes, you check them with your compass in hand, you retrace them in your mind, you copy the plan in your imagination, and you imprint it so well that it never entirely disappears.

Chronology, on the other hand, is a dry, laborious and thankless study, offering the mind nothing but off-putting dates and a prodigious multitude of numbers, which burden the memory, pile up with difficulty and easily slip away. But there seems to be some fault on the part of those who first set themselves up as masters of this important science, and if you are willing to delve into the depths of these difficulties, you will soon recognize that they do not have their origin in the very nature of the thing.

The object of Geography is the extent of the earth; the object of chronology is the succession of time. Can't duration be imitated and represented as sensitively and as distinctly as space, and can't [time] intervals be equally counted by degrees? It's hard to imagine what could prevent this: it's just as easy to measure years as it is to measure leagues, even simpler and easier in many ways.

1. The surface of the earth has two dimensions, length and width, which Geographers call Longitude and Latitude. The duration of time has only one, which is its length.

2. The ratio of degrees of Longitude to degrees of Latitude always increases or decreases from the Pole to the Equator, and from the Equator to the Pole, according to a certain progression that cannot be fully understood without some notions of Geometry and Astronomy; so much so that very few people are capable of surpassing a certain degree of mediocrity in Geography. Chronology does not have this disadvantage; freed from the servitude of the other sciences, it does not presuppose so much preliminary knowledge, and the interior of its sanctuary is not closed to anyone.

3. The figure of the Earth can only be faithfully represented on a Globe; the projection of any Map necessarily disguises it, and does not give a sufficiently accurate idea of it, and the World Map itself is more suited to making this error felt than to rectifying it. There is no similar illusion to be feared from a Chronological Map; it neither disguises nor alters its object in any way, and can be relied upon without scruple.

4. The divisions of space—leagues, stadia, miles—are arbitrary and variable; the divisions of time— days, months, years—are natural and constant, based on the observation of the regular periods of the Stars of the Firmament. If the lack of precision of the first observations of this kind often causes much torment to those who draw up chronological Tables, it causes none at all to those who study them; the great affair of the Scholars does not even cause a sensation to the Public; instead, the arbitrariness and diversity of geographical measures causes much more embarrassment to the Disciples than to the Masters.

5. A representative map of a place cannot exceed a certain size; only those that fit on a single sheet of paper are of any practical use, and rarely do we assemble more than four together, or if we do sometimes assemble more, they can only serve as parades, as their extremities are out of sight: We are therefore obliged to have a large number of different Geographical Maps, built on different scales, and to create at great expense what we call Atlas maps; general Maps with small dots for all countries, particular Maps with large dots for the details of these same countries, and the almost infinite variety of these scales does not fail to confuse a lot, and to cause a great deal of trouble, at least to beginners. Maps representing time can and should all be built on the same period, which constantly expresses years; and as this uniformity dispenses with the need to attach ratio scales, there is no need to study them with a compass in hand. Moreover, it's quite simple to assemble the entire length of these [time-]maps end to end, whether they're destined to adorn a long gallery, or whether you wish, according to the model I've given, to cover two cylinders arranged in such a way that one unwinds of its own accord as the other is rolled, thus imitating the revolution of the centuries. Thus, in one and the same machine, we have before our eyes a particular and detailed Map of the century whose history we are currently studying, and we have no less at hand the entire collection of these Maps, with all the ease imaginable of substituting one for the other at will, or to playfully unwind the whole succession of Empires and generations, sometimes descending from Adam to us, and sometimes going back from our time to that of creation, a little exercise to which children have been seen to indulge with pleasure, and which scholars themselves have not seemed to disdain. Everyone was surprised to see Chronology metamorphosed into Chronography, to see that a science of memory so cold, so sterile, so insipid, has become an amusing science, and so to say mechanical, which speaks to the eyes and the imagination, a moving and animated picture, where all the ages of the world pass in review, where each famous man comes to present himself in his rank with the attributes that are proper to him, where each Prince appears in the midst of his contemporaries and occupies the stage for more or less time, in proportion to the length of his reign; where the rise and fall of Empires are self-evident in a sensible form, without the trouble of making a study of them; finally, where all memorable events so strike the senses, are so easily arranged in the memory, and are so strongly imprinted on it, that we learn almost mechanically and without thinking too much about it.

Let's not, however, flatter ourselves to be able to tackle all the difficulties of Chronology at once; there are some difficulties that will never disappear, so inherent are they in the very essence of the thing. Just as we can boldly defy the most skilful Geographers to give us an exact description of certain uninhabited or even inaccessible countries, or even to tell us whether there are lands or seas that lie immediately beyond the poles, so it is not in our power to represent distinctly certain times absolutely devoid of good Historians, or even Historians of any kind: In the same way, there are countries, islands, lakes, rivers and mountains, mentioned by a small number of writers and travellers, and described in such a variety of ways that geographers, after having struggled to reconcile vague and often contradictory accounts, are obliged in the end to reject one and adopt the other; there are also centuries, Dynasties, whose memory is almost entirely erased, or whose facts are so mingled with fables that the small number of pieces reputed to be original have been drawn in so many different senses by Commentators, that is impossible to follow them all in their respective deviations, and to attach oneself to one of them without contradicting all the others.

But the difference that I find in this respect between Chronology and Geography, to the disadvantage of the former, is that the public, which has very little interest in distant and unknown regions, does not have the same indifference for times hidden in the night of oblivion, and that it seems on the contrary that the most distant and least known are those that most arouse its curiosity.

On the other hand, it can also be said that Geography, independently of its own disadvantages, participates in all those for which Chronology is, and ever will be, reproached. Indeed, Geography would be ill-advised to lend its torch to illuminate History, if it did not embrace the ancient and the modern in its scope, if it did not endeavour to represent as well the division of the Holy Land under Joshua, as its limits under the Empire of the Turks; if it did not take care to assign as positively the situation of the ancient Babylon long since destroyed, as of that which remains today, perhaps quite far from the ruins of the first. The public is no less curious to follow Hannibal's expeditions on the map than those of Tahmasp Qoli Khan [Nāder Shāh, the Persian warlord who seized the throne in 1736 and led spectacular campaigns from the Caucasus to northern India], and it is at least easy to determine the exact date of the Siege of Saguntum or the Battle of Zama [both events associated with Hannibal], as well as the position of the cities that these events illustrated.

The Chronographic Map I propose is made up of three large maps. The first covers all the periods from the creation of the world to the founding of Rome; the second extends from the founding of Rome to the birth of Jesus Christ; and the third from the birth of Jesus Christ to the present day. The reasons for this division must be explained.

The Christian Era is universally known among us, it is familiar to all of Europe, and it is from this era that all public and private writings are dated. With regard to times prior to the Vulgar Era, I have been struck by an important consideration: the time of the foundation of Rome is also considered to be constant, since which time there has been a fair degree of agreement on the main points, and chronology does not suffer from any major difficulties. The same is not true of the centuries that preceded this famous epoch; we have very few authentic monuments from these remote times, and scarcely any obscure and almost unintelligible fragments from a single secular historian like Sanchuniathon [a supposedly very early Phoenician historian whose work survives only in scattered Greek quotations], in which not even a single date is found. Moses is much older and infinitely more luminous; yet we must not expect our curiosity never to find anything to stop it in the Sacred History; it is a source of marvelous purity, but of immense depth, and the difficulty of combining texts and versions together is so great, that among orthodox Interpreters some place Moses himself fourteen centuries earlier, and others fourteen centuries later.

It is worth pointing out, however, that almost all the difficulties in the Holy Chronology concern only the estimation of years, and that there is general agreement as to the order of events; so that, in the impossibility I have found myself in, of satisfying everyone, I hope at least that most of the criticisms I will have to answer will fall rather on the figures of the scale which reigns throughout the length of my first Map, than on the choice or arrangement of the materials, which is undoubtedly what should interest us most.

In addition, I shall be greatly indebted to any scholars who take the trouble to send me their remarks by whatever means and in whatever form, and they will always find me willing to benefit from their enlightenment. As for those who are not well versed in History, I would ask them, as much for their own sake as for mine, to be careful not to make hasty decisions; as I have often corrected and reinstated the same date on several occasions, it could also happen to them to censure on the faith of one Author what would soon be justified by the testimony of several others. A famous modern writer (M. l'Abbé Langlet du Fresnoy.) has estimated the total number of History Books at thirty thousand folio volumes of a thousand pages each; I don't pretend to vouch for his calculation, but I dare to believe that there are few people in the world who can boast of having only gone through the tenth part of these Historical Monuments.᠅

Jacques Barbeu-Dubourg (1709–1779) was a French physician, botanist, writer, translator and publisher who designed a method of histographic visualizations which he called the Carte chronographique. He is also known for translating Benjamin Franklin's work into French and for inventing a gentlemen's umbrella fitted with a lightning conductor.

To learn more about Barbeu-Dubourg’s timeline, see:

Original essay and sheets at BnF Gallica https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1314025/f7.planchecontact.r=

Stephen Ferguson’s “The 1753 ‘Carte Chronographique’ of Jacques Barbeu-Dubourg.” The Princeton University Library Chronicle 52, no. 2 (1991). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26404421

Translation ©2025 RJ Andrews. All rights reserved.

Let me know if you can help improve this translation, or have suggested entries for future editions of THE SUMMER OF CLARITY.

About

RJ Andrews helps organizations solve high-stakes problems by using visual metaphors and information graphics: charts, diagrams, and maps. His passion is studying the history of information graphics to discover design insights. See more at infoWeTrust.com.

RJ’s book, Info We Trust, is currently out now! He also published Information Graphic Visionaries, a book series celebrating three spectacular data visualization creators in 2022 with new writing, complete visual catalogs, and discoveries never seen by the public.

this is hella cool

This is a truly remarkable timeline and mechanism! And the language of the text - 'delicacy does not dwell in the bosom of indigence' - is an added delight. Shouldn't you republish this scroll as a leporello with accompanying booklet?