When Fascists Chart

1940s Nazi information-graphic propaganda from Signal magazine.

Welcome to Chartography.net — insights and delights from the world of data storytelling.

Nazi Germany imposed its power through vigorous design: snappy uniforms by Hugo Boss, thundering vehicles by Mercedes and BMW, and monumental architecture built to make the common man feel small.

Did their use of design extend to information graphics? Maybe not—many of Germany’s best graphic minds fled. Pictorial-statistic Viennese landed in London after a Russian detour and created the Isotype Institute. Bauhaus veterans like Herbert Bayer escaped degenerate-accusations and found new opportunities to soar in America.

The Nazis were not playing with a full deck, but information warfare was surely too powerful of a weapon for them to abandon. Like other great powers, they must have churned out visually-rich statistical propaganda. Right?

Right.

Our distaste for the horrors of history can blind us to ways data-graphics are used for ill. While recent attention has been given to left-wing propaganda, particularly Soviet statistical atlases, we are lacking critical investigation of parallel right-wing efforts.

In hopes of spurring that interrogation, we present a selection of choice Nazi information-graphic propaganda from Signal magazine.

You may, like us, find them creative or imaginative or even appealing. That’s their job: to attract and sustain attention while they warp your world view. We should be on the alert for such efforts.

Signal magazine, 1940–1945, was a propaganda tool of Nazi Germany, published under the close supervision of the Propaganda Ministry of the Wehrmacht armed forces. It was issued about every two weeks and distributed in 26 languages, including German, English, Iranian, Greek, and Hungarian. Signal, a foreign influence operation, was not available commercially in the Third Reich. It was soon banned in the United States and England.

The magazine was the brainchild of colonel Hasso von Wedel, chief of the Wehrmacht Propaganda Troops. Its look was based on America’s Life magazine. Its content was significantly influenced by Paul Karl Schmidt, the press officer of the Foreign Office whose specialty was the "Jewish question"—the debate about the status and treatment of European Jews. Signal surprisingly contains almost no anti-Semitic content, perhaps because it did not want to offend intelligentsia in its target countries. Instead, it favored portraying Germany in an extremely friendly, kind, peace-loving, almost liberal light.

The magazine was primarily intended for citizens of the Axis powers, the population of German-occupied territories, and parties in the Entente countries that sympathized with Nazi ideology. Its articles and pictures proclaimed the greatness of Germany, the peace of a Europe unified by the Germans, the heroism of the Wehrmacht, and the enthusiasm of the population “liberated” by Germany. These themes were interwoven with articles on modern women's lifestyle, fashion, cars, popular science, the ideal family model, and a sporty lifestyle. Turn its pages and you encounter strong-jaw soldiers, beautiful young women, and lots of cute babies living in utopian whites-only harmony—a fascist’s dream. Life itself wrote that Signal was a “great arsenal of Axis propaganda.”

The first issue in April 1940 had a circulation of only 136,000 copies, but by mid-1942, its global circulation had reached nearly 2.5 million. Compared to other magazines of the time, the production costs of Signal were enormous, amounting to more than 20 million German Reichsmarks annually by 1943. Converted to about $8m 1943 America dollars, that amount could buy hundreds of Sherman tanks.

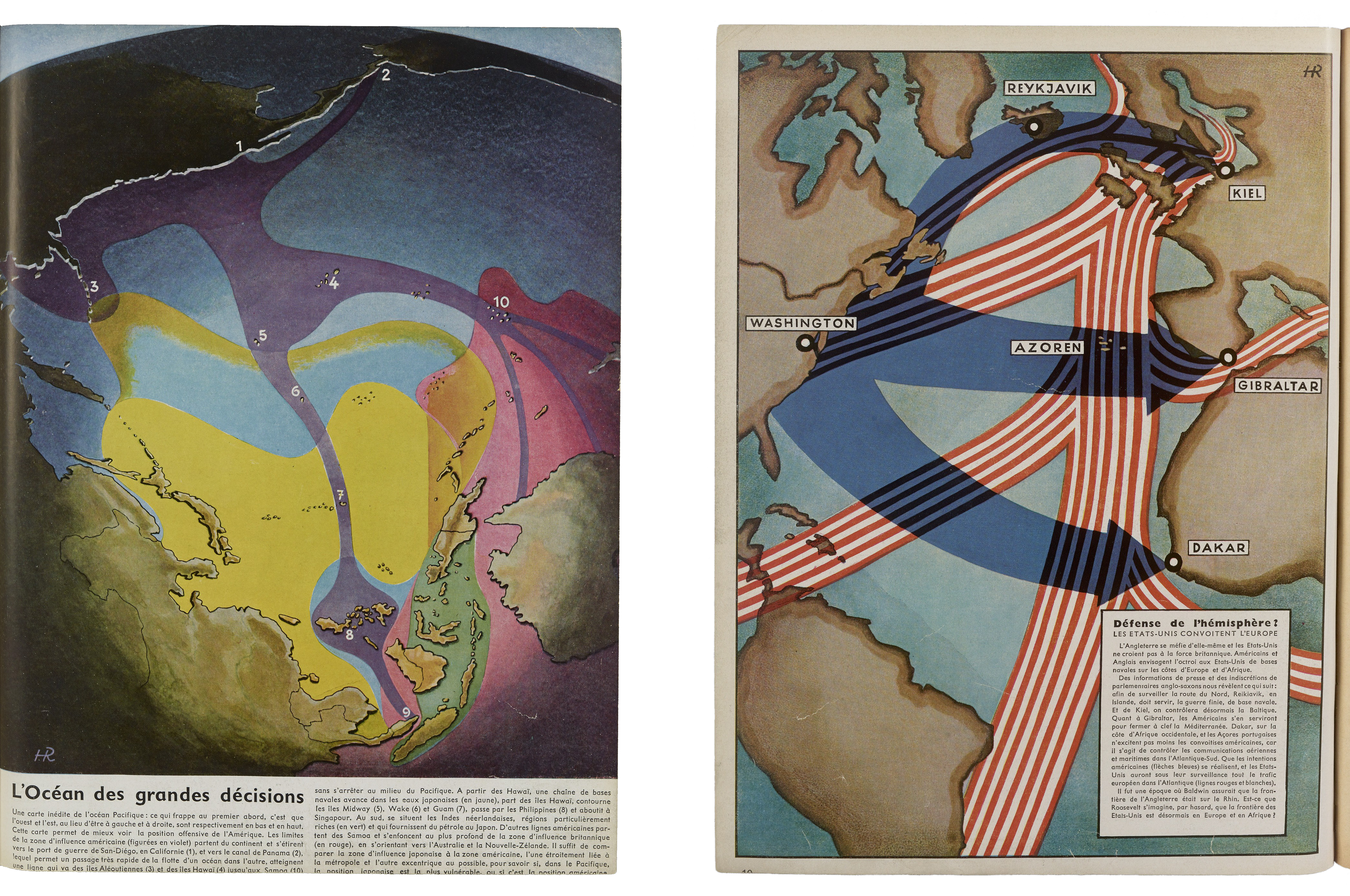

Across English and German literature written about Signal (see our notes at the end), no one has highlighted its maps, diagrams, and charts. Their graphic quality is reminiscent of the contemporary Life and Fortune magazines. Some maps bring to mind Richard Edes Harrison. The simple red and black lines of many maps is reminiscent of the work of radical left-wing/communist activist cartographers of the time including the Hungarian Sándor ‘Alexander’ Radó, British J.F. Horrabin, and Polish Marthe Rajchman. You may even see the influence of Herbert Bayer in Signal.

Wages accounted for about half of its budget. Signal employed leading journalists, experts, analysts, photographers, and graphic designers. One of the most distinctive graphic styles of Signal was that of the artist with the initials HR, who is sometimes referred to in the text as R. Heinisch. He can probably be identified as Rudolf Heinisch, an expressionist graphic artist and painter who was banned as a “degenerate artist” by the Nazis. He is known to have worked as an illustrator for the publisher Ullstein Verlag after 1933. His maps and infographics deserve separate research.

Bird's-eye view maps and information graphics by painter and graphic artist Karl Friedrich Brust are also noteworthy. Other important contributors to Signal’s graphic design were Hans Kossatz, Helmuth Ellgaard, Hans Liska, Walter Goetschke, and Leo von Malachowski. For many of these artists, their only means of survival inside Nazi Germany was to sign with publishers and partially serve Nazi propaganda. In addition to Signal, their work can also be found in other publications by Deutscher Verlag, such as the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung and Das Reich.

Signal’s last issue, 1944 #11, was published as allied forces began fighting into Germany.

—Attila and RJ

Notes

All graphics from the French edition of Signal via BnF.

S.L. Mayer – The Best of Signal, Hitler’s Wartime Picture Magazine. New York: Gallery Books, 1984

Rainer Rutz – Signal: Eine deutsche Auslandsillustrierte als Propagandainstrument im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Essen: Klartext Verlag, 2007

Jeremy Harwood – Hitler’s War. World War II as Portrayed by Signal, the International Nazi Propaganda Magazine. Minneapolis: Zenith Press, 2014

Jason Forrest — Data Visualization in the Age of Communism, Nightingale, 2019.

About

Attila Bátorfy is a Hungarian information designer and head of project of Átlátszó’s visual journalism project Átló. He is also master teacher of journalism, media studies and information graphics at the Media Department of Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest. Learn more at attilabatorfy.com.

Bátorfy previously contributed to a Chartography on historic Hungarian data graphics.

RJ Andrews helps organizations solve high-stakes problems by using visual metaphors and information graphics: charts, diagrams, and maps. His passion is studying the history of information graphics to discover design insights. See more at infoWeTrust.com.

RJ’s book, Info We Trust, is currently out now! He also published Information Graphic Visionaries, a book series celebrating three spectacular data visualization creators in 2022 with new writing, complete visual catalogs, and discoveries never seen by the public.